For a number of years I worked alongside writer Terry Deary, helping him to research a number of the Horrible Histories titles. In this article you will discover the secrets I learned that allow me to quickly research information that could be used to write books. You will also discover how to focus your efforts so that you use your time well to find the facts you need to take your book to the next level.

For a number of years I worked alongside writer Terry Deary, helping him to research a number of the Horrible Histories titles. In this article you will discover the secrets I learned that allow me to quickly research information that could be used to write books. You will also discover how to focus your efforts so that you use your time well to find the facts you need to take your book to the next level.

The two most common mistakes I come across when teaching writers to research are as follows:

- Knowing what you don’t know: Most writers embark on the process of research with a scattergun approach. They often delve into a subject, quickly becoming bogged down with the vast swamp of detail. It is a better approach to take a step back, get a feel for the topic and then define what you don’t know.

- Having a system: It is not uncommon to see writers researching in a haphazard and makeshift nature. One of the biggest lessons I took away from researching for the Horrible Histories series, was that research is a job with a defined goal. You are often looking for specific information and it is better to have a system that allows you to find this information quickly, rather than approach the issues with your fingers crossed, searching though masses of sources hoping you will stumble on what you need.

This article spells out a system that will allow you to define the information you are looking to find and then show you a way to find this with the least effort.

It is essential to recognise that there are two types of research: General and Specific.

General Research

This is all about gathering a wider knowledge of the subject of your novel or book. In fact, to be more precise, this is about discovering what you know, and more importantly, what you don’t know.

- Read general books: Start with outlines and histories of the period (topic) under study. Get a feel for the key events of the time. Read books at all levels. Children’s history books are often a good place to start since they will give you a nice overview.

- Read ‘real’ history books: The next stage is to read some serious history books. Find out who the key historians are in the area of your research and read a couple of their books. Good history books will have loads of references to the sources that the historians used in their research. You can use these references to find more history books.

- Beware of the Internet: At this stage you are still gathering a deeper knowledge of the subject area. You may find that the Internet is not the most helpful tool, since it will tend to focus on defined information and facts. This said, I often found Wikipedia a great place to clarify details.

- Make notes: This is very important. As you read, make notes of the key points and, most importantly, write down questions.

Specific Research

Having gathered a general knowledge you will now be ready for specific research. At this point you are looking to define what you don’t know. This is all about answering the questions that will help with your writing. However, the key is to be specific.

Let’s say you are writing a scene set in London in 1867. You have a young couple walking down a street at night.

You could ask:

‘In Victorian Britain what did a London street look like at night?’

This would be fine but it is very hard to answer. Where would you begin? You would be very lucky to find a website or book that would give you the description you needed.

OK - let’s change the question to:

‘In 1867 what did a London street look like at night?’

This is a more specific question and therefore easier to research. You might do a Google search on ‘London streets 1867’. This might pull up some useful information.

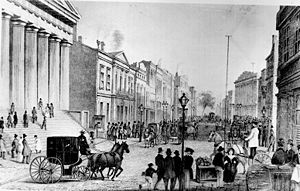

An image search I did produced this picture:

The picture shows lampposts, but your general research should have told you that gas lighting was introduced into London at some point during your period. Since you can’t be sure what year the picture was produced, you can’t be sure that gas lighting was being used in 1867.

So the question now becomes:

‘In what year was gas lighting introduced to London?’

A Google search on ‘gas lights London introduction’ brings up this Wiki page:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gas_lighting

If you hit Ctrl F you can bring up a search box in your browser. Now type in ‘London’ and keep scrolling through.

Soon you get to this paragraph:

The first public street lighting with gas took place in Pall Mall, London on January 28, 1807. In 1812, Parliament granted a charter to the London and Westminster Gas Light and Coke Company, and the first gas company in the world came into being. Less than two years later, on December 31, 1813, the Westminster Bridge was lit by gas.

You would now be able to confidently describe gas lighting in your novel’s narrative. Though this might not be the full answer, since you are not sure just how widespread lighting was by 1867, you can see the process.

The key to effective specific research is good general research. The hours spent reading will give you the knowledge you need to ask the correct specific questions.

Sources to answer good specific questions include:

- Google: This is the number one search engine for a reason. The key is to be creative with your search terms. Time spent learning advanced search terms and techniques will be well spent.

- Books: You may find that there are whole books written that will answer your question. Type ‘London gas light’ into Amazon to get the general gist.

- Professionals: It sometimes pays off to be cheeky. Don’t be afraid to contact key professionals that you think might be able to answer your questions. Many will be more than happy to help a writer.

- Friends: Don’t forget you real and internet friends. If you have a question than ask people if they can help - you never know.

The result of this system is that you can define your research into a series of questions. Once you have the broader general understanding, you can use specific questions to tease out relevant details. This means that you will never waste time blindly hoping to stumble on the answers your need, but will instead have a laser like focus the source mostly likely to bring the answers you seek.

Apr 2013